- home

- Bandhani

- region

- raw material

- popular dyes for bandhani

- designs

- process of bandhani

- change in bandhani

Dyed Textile- Social Significance in Culture of Rajasthan

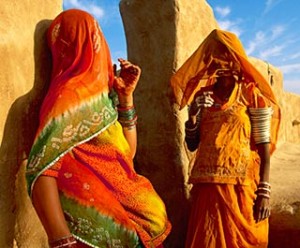

The tie-dyed chunari or odhani, (the cloth worn over the head and shoulders), symboloises womanhood and marriage. Fine muslins, georgette and chiffons in novel colour-schemes are basically the preserve of the urban banya, mahajan or merchant community. The women of the Bishnois, vegetarian agriculturalists of Western Rajasthan are recognisable by their red skirts printed with black circles and their tie-dyed red odhanis edged with black, while those of Sind,the desert region that stradles the Pakistani border, wear distinctive large odhanis of coarse rust-coloured cotton with simple linear patterns of white dots. While the villages of western Rajasthan around Barmer and Jaisalmer, and the Sind area of Pakistan, traditionally produce some of the simplest tie-dyed designs, the same technique of making patterns from a series of dots or squares was also used to spectacular effect in urban centres to the east of Rajasthan, such as Jaipur, Kota, Ajmer and Alwar.

The highly decorative chunari designs were used for turban cloths (pag) and women's head- cloths (odhani of dupatta). Jodhpur is a  centre for skilled bandhani work. Another, less well-known,area of bandhani production is centred around Udaipur and includes nearby Nathadwara and Chitor, where subdued odhanis in dark reds and purple, tie-dyed with simple designs in white dots are made: Further east, in Sawai Madhopur, striking abstract tie-dyed designs on coarse dark brown cotton are worn by local Mina tribeswomen. In spite of the large number of bandhani centres throughout Rajasthan, it is the state capital, Jaipur,that has probably best retained its reputation as a tie-dyeing centre, both for chunari and lahariya cloths.

centre for skilled bandhani work. Another, less well-known,area of bandhani production is centred around Udaipur and includes nearby Nathadwara and Chitor, where subdued odhanis in dark reds and purple, tie-dyed with simple designs in white dots are made: Further east, in Sawai Madhopur, striking abstract tie-dyed designs on coarse dark brown cotton are worn by local Mina tribeswomen. In spite of the large number of bandhani centres throughout Rajasthan, it is the state capital, Jaipur,that has probably best retained its reputation as a tie-dyeing centre, both for chunari and lahariya cloths.

Even today its thriving cloth bazaars are full of both traditonal and new bandhani designs, as well as the block-printed outside India. The men would put on turbans tied according to their community or regional style, with specific patterns for particular occasions: lahariya during the rainy season; pink, red and green patterns (chunari or otherwise) for any festive event, or the panchrang pag in yellow, red, green and two shades of blue.

Sombre occasions, including periods ofmourning, were marked by duller colours such as mauve and brown, often in a discreet bundi (dot) patterrn or tiny mothara (check), formed by tying the turban-cloth on the opposite diagonals. Whether in men's turbans or women's odhanis, the finest and most complicated patterns were always dyed in fugitive colours. The coarser cloths with simpler patterns were made in fast (pakka) dyes, and were considered much less desirable. The fast colours were duller, and worn by widows and those who couldnot afford the finer workmanship of the kachcha pieces. The adoption of Pakka rang clothing during widowhood or bereavement does carry more significance than a simple change from colourful clothing to sombre. It may also be true that the many festivals of the Hindu calendar demanded more new gar ments than many people could afford, and renewable dyes provided a change of costume without the expense of buying a new one.